Affect

“Affect is in the driver’s seat and rationality is a passenger. It doesn’t matter whether you’re choosing between two snacks, two job offers, two investments, or two heart surgeons—your everyday decisions are driven by a loudmouthed, mostly deaf scientist who views the world through affect-colored glasses.” — Lisa Feldman Barrett1

Words influence the way we think.2 Here’s one we don’t hear every day: Affect. However, if we understand what it means and start to incorporate this word into our everyday speech, we may become more fluent in the wisdom of our bodies and less troubled by its signals. Learning to coassemble affect with cognition will help us become better informed and smarter.3

The neuroscientists who dedicate their lives to understanding why we feel often use this word. Antonio Damasio: “When our brain sums up what is happening with our body moment by moment, we feel that summary as affect.” Mark Solms says affects make demands upon the mind, and that cognition performs the work so demanded.4 Lisa Feldman Barrett writes, “Affect is not just necessary for wisdom; It’s also irrevocably woven into the fabric of every decision.”5

An Everyday Decision. Delayed gratification came up recently in a conversation with a young friend of mine. He said that lately, he had been concerned about his ability to delay gratification. I thought he was kidding; he is one, if not the, most responsible person I know.

He continued, saying he had recently purchased new monitors. He had wanted them for a while, then waited; he wanted them for a while longer, then waited even longer. Finally, he bought them.

What’s the problem?

Feeling. The decision didn’t leave him feeling good. Why? (… !) He has given himself a budget. Although he already has more than three months’ worth of living expenses saved up (psst! he’s eighteen …), he went over budget by purchasing these monitors, and “It wasn’t the first time,” he said. He had just bought a camera for his car.

First, I reminded him that just days (the day?) after he purchased the camera, someone hit his car. The camera provided evidence that the accident wasn’t his fault, potentially covering its cost. He immediately felt relief.

Regarding the monitors, we had no choice but to acknowledge that he feels troubled. I suggested that he interpret his feelings as a form of feedback.

Affect.6 Damasio says that feeling is the critical piece in a collection of processes that includes drive, motivation, and emotion, and that the term “affect” is the broad tent that covers this collection of processes.7

Barrett describes affect as our simplest feeling, which continually fluctuates between pleasant and unpleasant (valence) and between calm and tense (arousal).8

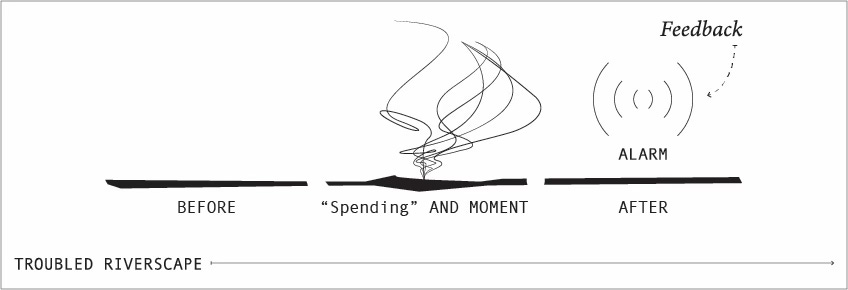

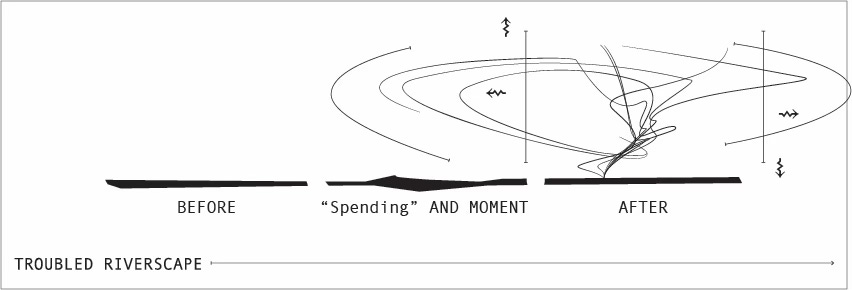

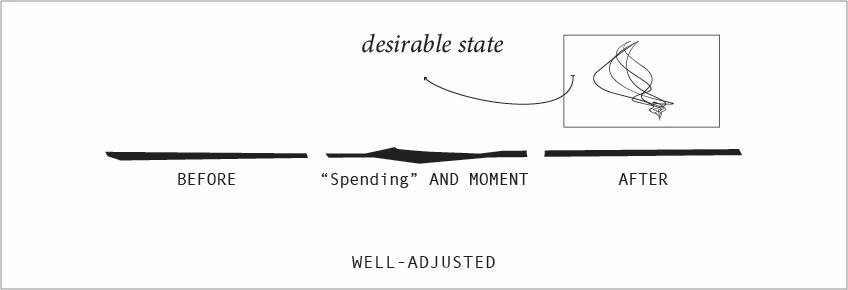

Before his “Spending” AND Moment, my friend was satisfied and on budget. During his AND Moment (while two wants opposed one another: buying new monitors and staying within budget), he was frustrated with his old monitors and decided to replace them. After reviewing his numbers later, he became very distressed to face the evidence of going over budget.

I suggested his feelings are not meant to punish him. Instead, they serve as a signal, reminding him of how deeply he values staying within his budget. Affect, an extended form of homeostasis, insists that we remain within our magic range.9

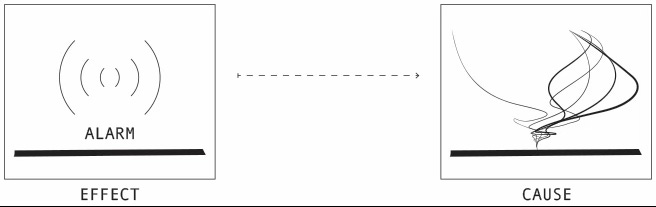

Troubled feelings drive us to identify their cause.10 Why? Because it won’t be long before we have another similar decision to make. So, should we do the same thing? Or choose differently next time?

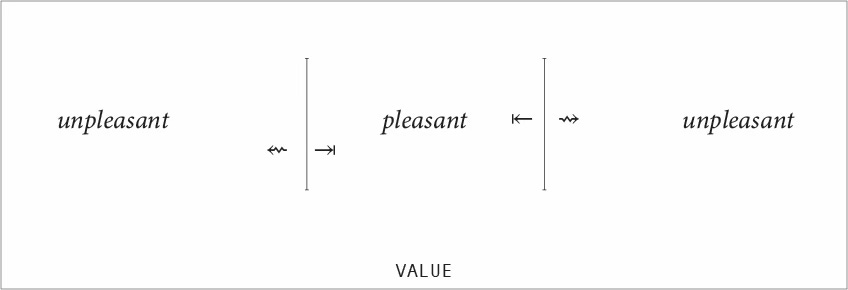

Future choices must be based on a solid value system that helps us differentiate between what is beneficial and what isn’t, both now and in the future. Without this foundation, we are rudderless.11 A property of affect is valence. Our future decisions are primarily influenced by the emotional outcomes of past actions. This is the essence of the Law of Affect. By allowing feelings to guide our behavior, we gain an adaptive advantage over automatic responses, enabling us to navigate more effectively.12

Value. Valence varies from pleasant to unpleasant and reflects the fundamental value system that underpins our lives.13 For example, good health is often regarded as beneficial while its absence is seen as unbeneficial. Even if we are not fully aware of it, our choices tend to be swayed by their potential impact on our future selves. No matter how unaware we are of these influences, we are still driven by the personal emotions tied to biological values.14

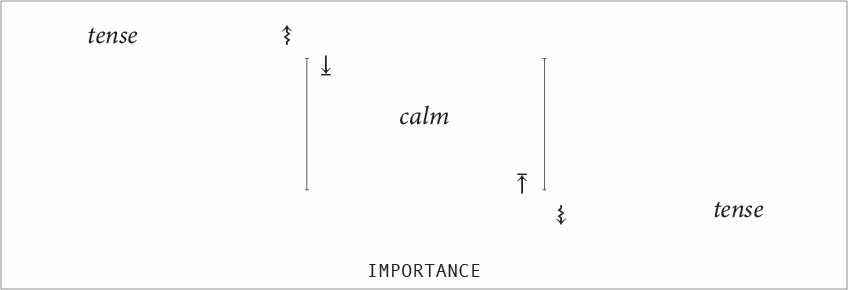

My friend highly values the financial health of his future self, whether consciously or not, believing it affects his overall well-being and survival. His internal alarm signal warned him that if he continued on this path, it would lead him in a direction he’d rather not go. He felt this urgently, which brings us to the second property of affect: arousal.15

Importance. Arousal is a basic feeling that you experience constantly, ranging from calm to tense.16

Valenced affective cues are information. They tell us what we value. Arousal provides information about the urgency or importance of a situation.17

Measured Choices. My friend feels outside of his magic range.

Learning from experience is how we remain within.

Affects are closely linked to drives, representing their emotional expression. They help us understand how well or poorly we align with our values. Our capacity for psychological freedom, pertaining to our ability to make our own choices and shape our lives, is determined by the interaction of both our cognitive and affective systems.18

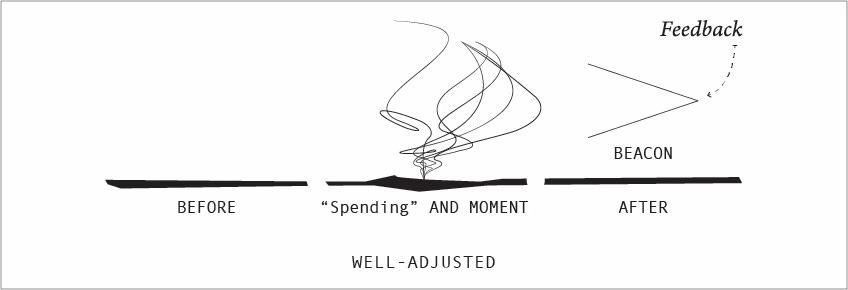

The next time my friend has to make a purchasing decision, he can rely on his memory to recall how he felt after his last decision. This process helps stabilize his emotions and turn them into cognitive reasoning. His feelings have impacted his thought process, and he will need to put in the effort to ensure that his next decision aligns with his budget.19 It’s this or the habituation problem.

The Habituation Problem. I encouraged my friend to recognize the importance of his feelings rather than be troubled by them. When we equate “calm” as good and “tense” as bad, we tend to try to escape our feelings and become dull to them. Then we have a bigger problem on our hands: habituation.

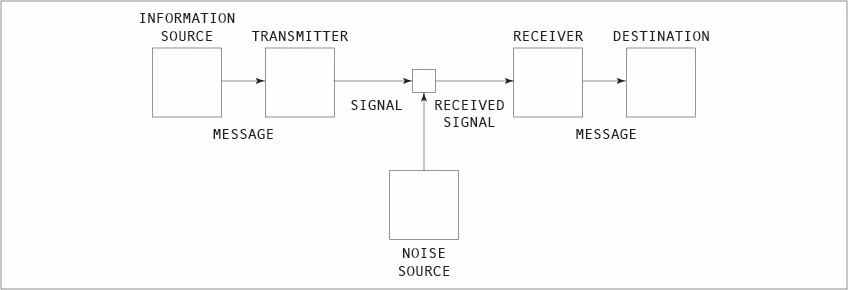

Information theory helps us understand behavioral plasticity. In a monotonous environment (lacking change), one in which we make the same decision over and over again, we lose arousal and become less alert. High-information promotes arousal. Feelings of distress are high-information, raising our arousal and demanding our conscious cognition, as opposed to creating unwanted effects as a result of habitual behavior.20

Behavioral Change. Guided by our feelings, affect both accompanies and becomes cognition. The ‘work’ we do is to inhibit automatic action tendencies and stabilize intentionality.21 That way, next time, we feel a beacon guiding us forward, rather than an alarm. “Feed-back” is the return of energy from output back to input.22

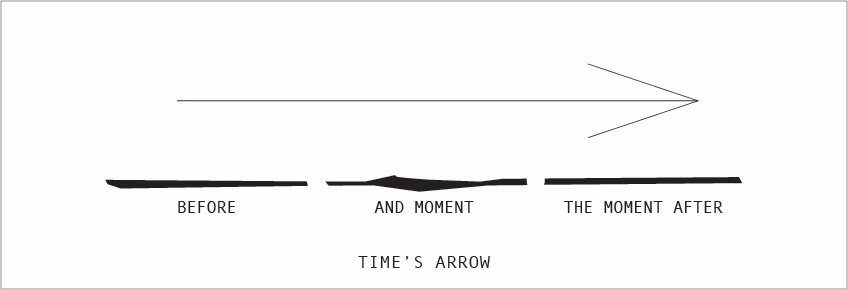

This is how we feel our way to flourishing and perhaps, even time’s arrow for our lives.23

“We are but whirlpools in a river of ever-flowing water. We are not stuff that abides, but patterns that perpetuate themselves. A pattern is a message, and may be transmitted as a message.” — Norbert Wiener

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt., hereafter cited as HEAM | p 80

“Words seed your concepts, concepts drive your predictions, predictions regulate your body budget, and your body budget determines how you feel.” — Lisa Feldman Barrett

Rodger, T. F. (1963). Affect Imagery Consciousness. By Silvan S. Tomkins Vol. 1V. Cognition. New York: Springer, hereafter cited as AIC-IV | p. 7, “Affects coassembled with cognitions become better informed and smarter.”

Solms, M. (2021). The hidden spring: a journey to the source of consciousness. hereafter cited as HS

HEAM | p 80

Scott’s email after reading this post: “What does affect mean again? Just kidding... No, really, what does it mean?????”

Keynote Dr. Antonio Damasio - About The Psychology of Feeling | 18:58

HEAM Glossary | Affect: Your simplest feeling that continually fluctuates between pleasant and unpleasant, and between calm and jittery.

HS | p 302, “Affect is an extended form of homeostasis, which is a basic biological mechanism that arose naturally with self-organisation. Self-organizing systems survive because they occupy limited states; they do not disperse themselves.”

HEAM | p 75, “When you experience affect without knowing the cause, you are more likely to treat affect as information about the world, rather than your experience of the world.”

HEAM | p 80, “Robbed of the capacity to generate interoceptive predictions, Damasio’s patients were rudderless.”

HS | p 100, “Choices can be made only if they are grounded in a value system – the thing that determines ‘goodness’ versus ‘badness’. Otherwise, your response to unfamiliar events would be random. This brings us full circle back to the most fundamental feature of affect: its valence. You decide what to do and what not to do on the basis of the felt consequences of your actions. This is the Law of Affect. Voluntary behaviour, guided by affect, thereby bestows an enormous adaptive advantage over involuntary behaviour: it liberates us from the shackles of automaticity and enables us to survive in unpredicted situations.”

HEAM Glossary | Valence: A basic feeling that you experience constantly, ranging from pleasant to unpleasant. A property of affect. || HS || p 96-97, “Valence reflects the value system underwriting all biological life, namely that it is ‘good’ to survive and reproduce and ‘bad’ not to do so.

HS | p 96-97, “What motivates each individual is not these biological values directly, of course, but rather the subjective feelings they give rise to – even if we have no inkling of what the underlying biological values are, and even if we do not intellectually endorse them.”

HS | p 135, “This is another reason why I prefer the term ‘arousal’ over ‘wakefulness’ or ‘level’ of consciousness. ‘Arousal’ accommodates (even positively suggests) emotional responsively and intentionality, which, as we see here once again, lie at the heart of conscious behaviour. Affective arousal enables volition.”

Thayer, R. E. (1990). The biopsychology of mood and arousal. Oxford University Press. | p 7 & 8, “Energetic arousal and tense arousal, as I call the two major mood systems, represent two very basic mood-behavior orientations. […] With activation of the tense arousal system, however, there is not only preparation for action, but also restraint or inhibition. […] In a sense, these two mood systems are represented in consciousness as two kinds of subjective energy. One of them is called ‘tense-energy’ and the other ‘calm-energy.’”

Storbeck, J., & Clore, G. L. (2008). Affective arousal as information: How affective arousal influences judgments, learning, and memory. Social and personality psychology compass, 2(5), 1824-1843. | “We conclude that whereas valenced affective cues serve as information about value, the arousal dimension provides information about urgency or importance.”

HS | p 98, “Now you see how closely affects are tied to drives; they are their subjective manifestation. Affects are how we become aware of our drives; they tell us how well or how badly things are going in relation to the specific needs they measure.” | AIC-IV | p 361, “Psychological freedom is the power to determine one’s own choices, one’s own actions, and one’s own life. For Tomkins, the human being’s capacity for psychological freedom was a joint function of the complexity of both the cognitive and the affect systems.”

HS | p 220, “Working memory is literally the holding in mind of feeling—stabilized affect transformed into cognitive work … if affect is demand made upon the mind for work, then conscious cognition is the work itself. Thus, affect both accompanies and becomes cognition.”

Pfaff, D. W. (2006). Brain arousal and information theory: neural and genetic mechanisms. Harvard University Press. | p 19, “I further argue that information theory plays directly into the understanding of one of the most important types of behavioral change, a prominent form of ‘behavioral plasticity.’ Let’s turn directly to the role of information theory in brain arousal. It is brutally clear that in a monotonous environment, lacking change, a human or animal will lose arousal and will become less alert. While change, uncertainty, and unpredictability—high-informaion environments—promote arousal, the lack of these environmental features decreases it. […] I would reformulate the ‘habituation problem’ from being simply the neurobiology of a type of learning to being an example of the general neurobiology of informational change.”

HS | p 220, “The ‘work’ in question entails inhibition of automatic action tendencies and the stabilizing of intentionality while the system feels its way through unpredicted problems… affect is nothing other than the announcement of salient need.”

Gleick, J. (2011). The information: a history, a theory, a flood. Pantheon Books, hereafter cited as TI | p 238, “To analyze it properly, he borrowed an obscure term from electrical engineering: ‘feed-back,’ the return of energy from a circuit’s output back to its input.”

TI | p 270, “He came up with the word entropy, formed from Greek to mean ‘transformation content.’” || HS || p 155, “Entropy may in fact be the physical basis for the fact that time itself appears to have a direction and flow.” ||| Gleick, J. (2017). Time travel: A history. Vintage. ||| p 117, “In Minkowski’s world, past and future lie revealed before us like east and west. There are no one-way signs. So Eddington added one: ‘I shall use the phase ‘time’s arrow’ to express this one-way property of time which has no analogue in space.’ He noted three points of philosophical import: 1) It is vividly recognized by consciousness, 2) It is equally insisted upon by our reasoning faculty, 3) It makes no appearance in physical science except . . . Except when we start to consider order and chaos, organization and randomness.”