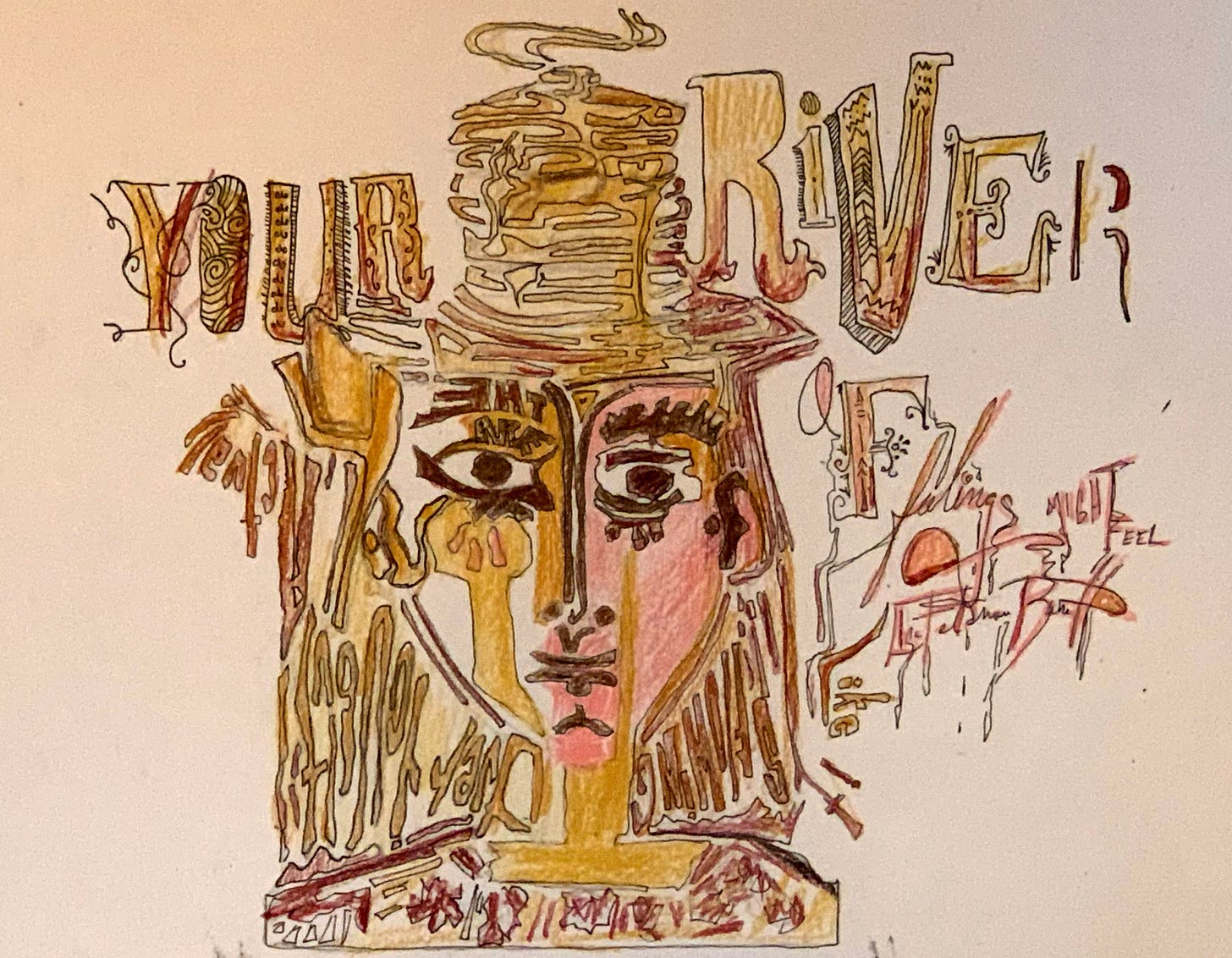

“Your river of feelings might feel like it’s flowing over you, but actually you’re the river’s source.”

— Lisa Feldman Barrett, How Emotions are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain1

The origin of the word rival, from the Latin rivalis, describes the competition between those that use the same river—the same resource.2 When rivals are equally matched, who wins?

It’s 10 a.m. You are sitting in a booth at a diner with your family checking out the menu. Last night, you told yourself that you would choose something “light.” You love pancakes. The diner you are in specializes in pancakes. The best pancakes. World famous. You can eat a stack of pancakes with your eyes closed. In fact, you have. But you have a goal to lose weight, just enough to “feel good in your clothes,” and even the best pancakes won’t help you reach it.

Uncertainty. We announce a goal when we have the resolve to achieve it. We are driven. Then, on any given day, our circumstances change, frustrations accumulate, and consequently, we feel discouraged.3 Our shifting energy cycle, and the interaction of this cycle with tension, can produce a measure of time on our riverscape when we are less certain about our ability to reach our goal.4 When we’ve lost energy, our mood adds to the noise, and the effect is—increased uncertainty.5 In the presence of a want that can negate our goal, we feel uncertain of why, or importantly—IF—the goal is worth the effort of resistance.6

Then again, our decision-making can be influenced by positive moods.7 Resistance is effortful work. It costs energy we may not feel like spending no matter what the mood.8

When resolution dissipates into uncertainty, we are in an AND Moment, a moment when our river of time flows between equally matched rivals. One rival wants to maintain a goal or value. The other wants something that opposes that goal or value. The problem? They are both using the same resource. Namely—you9

Drive is “a measure of the demand made upon the mind for work in consequence of its connection with the body.”10 Bodily needs become mental energy.11 But this energy is capable of decreasing, weakening, and getting lost. It can become unavailable. It can be useless.12

“The ‘usefulness’ of energy is defined by its capacity to perform work.”13

X. X is something extra we perceive from our choices and actions. If pancakes and syrup are what we want, we pass on them because we want to receive something extra. And, importantly, it is not merely weight loss or feeling good in our clothes. It’s also the sense of well-being and achievement that can lead to a profound change in attitude and self-efficacy over time. We highly value X.

Achieving X can create an energy source to continue learning from experience. Not achieving it can produce drive.14

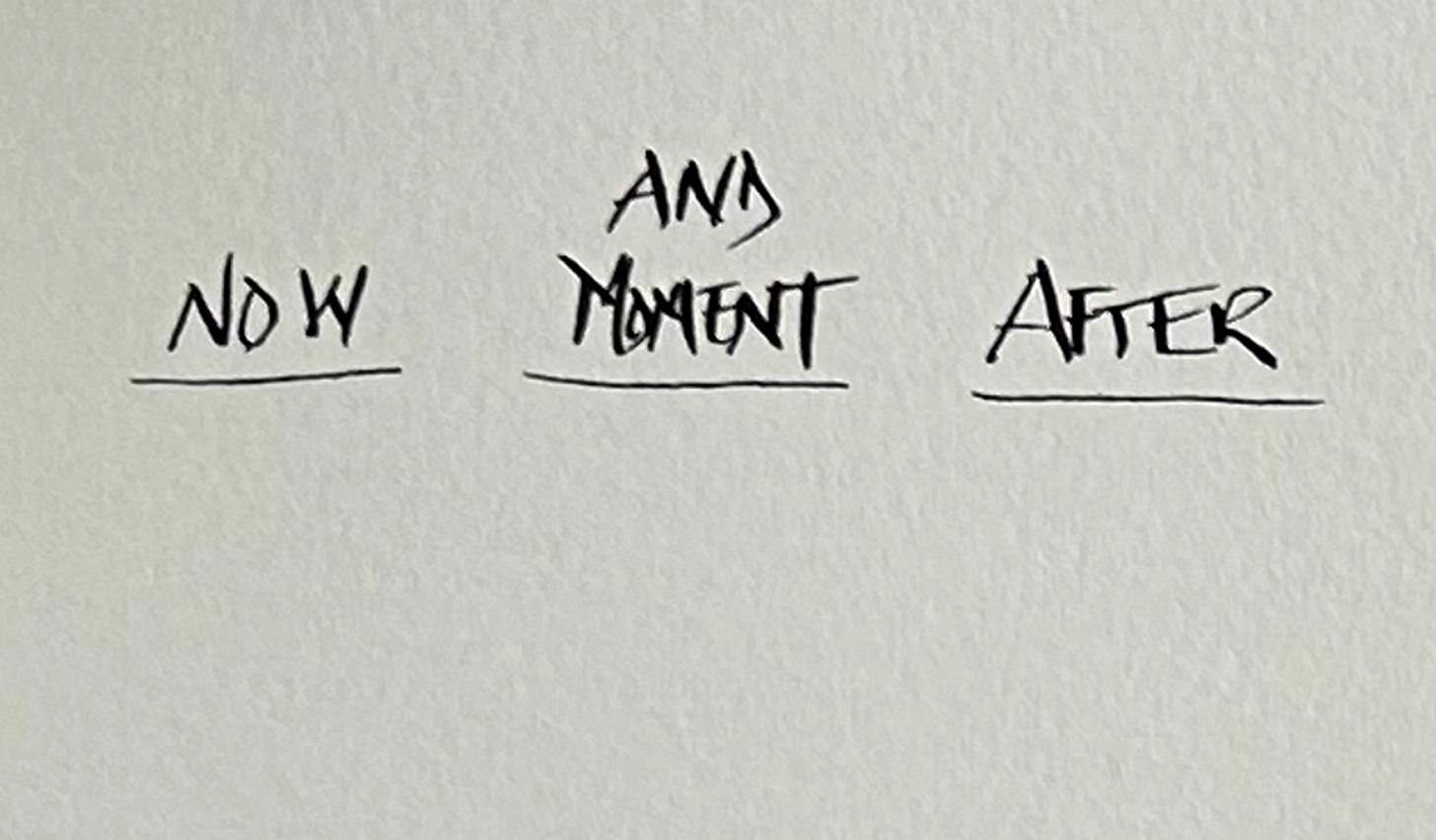

“Breakfast” AND Moment. We can illustrate a river of time by drawing three sequential lines and labeling them NOW, AND MOMENT, and AFTER.

The first line represents the present. By understanding where we stand, we can map out our future course of action. Alan Watts said, “Everyone automatically assumes that the present is the result of the past. Turn it around, and consider whether the past may not be a result of the present. The past may be streaming back from the now, like the country as seen from an airplane.”15

Rivals. The middle line is the AND MOMENT, and the third line represents AFTER. Let’s call “feel good in clothes” Future Want and “pancakes and syrup” Present Want. In our story, Future Want and Present Want are rivals, and their positions are firmly staked on opposite sides of our river, each using the very same resources. That is—your energy. Future Want desires to maintain your goal. Present Want craves a stack of pancakes.

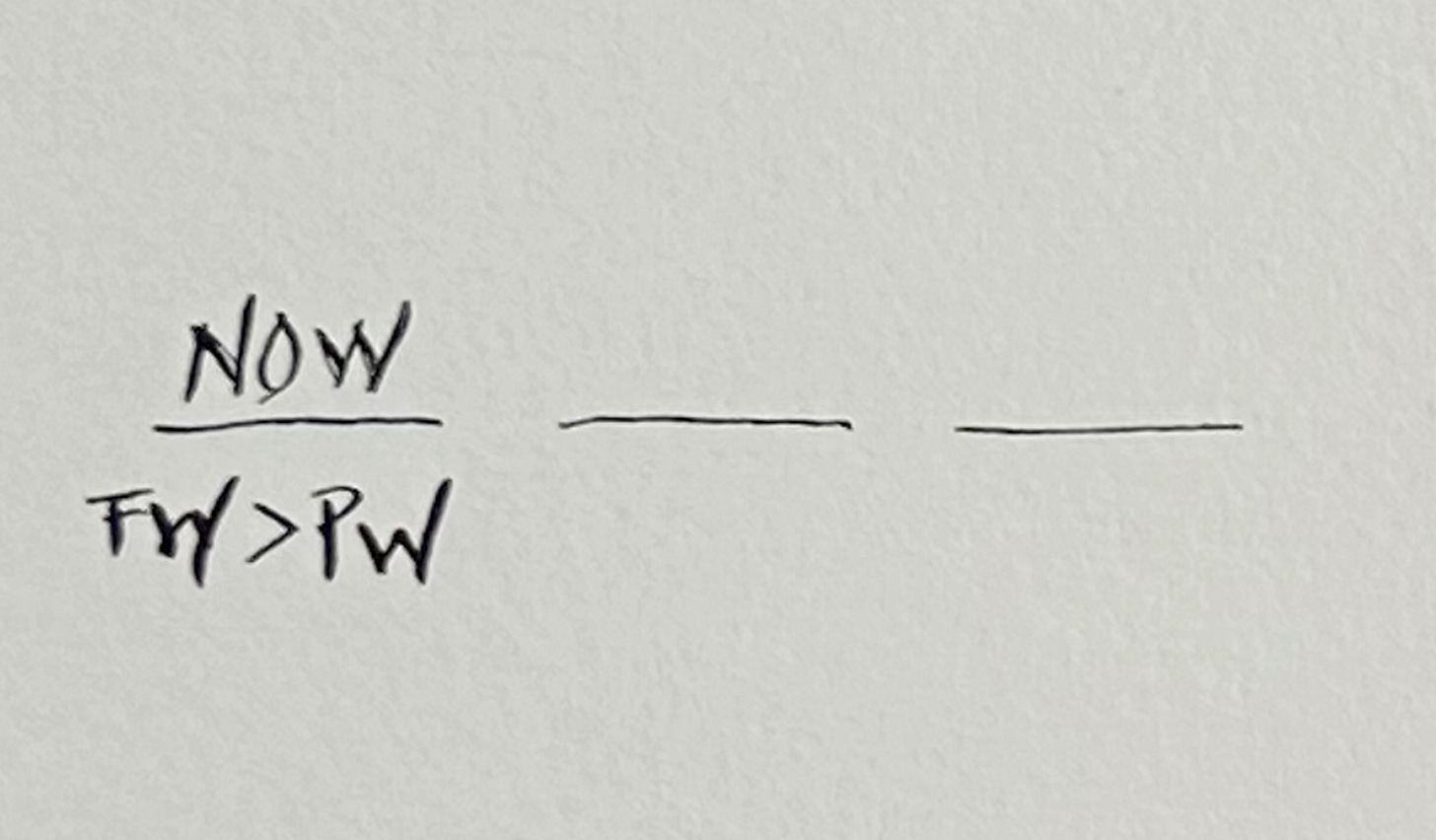

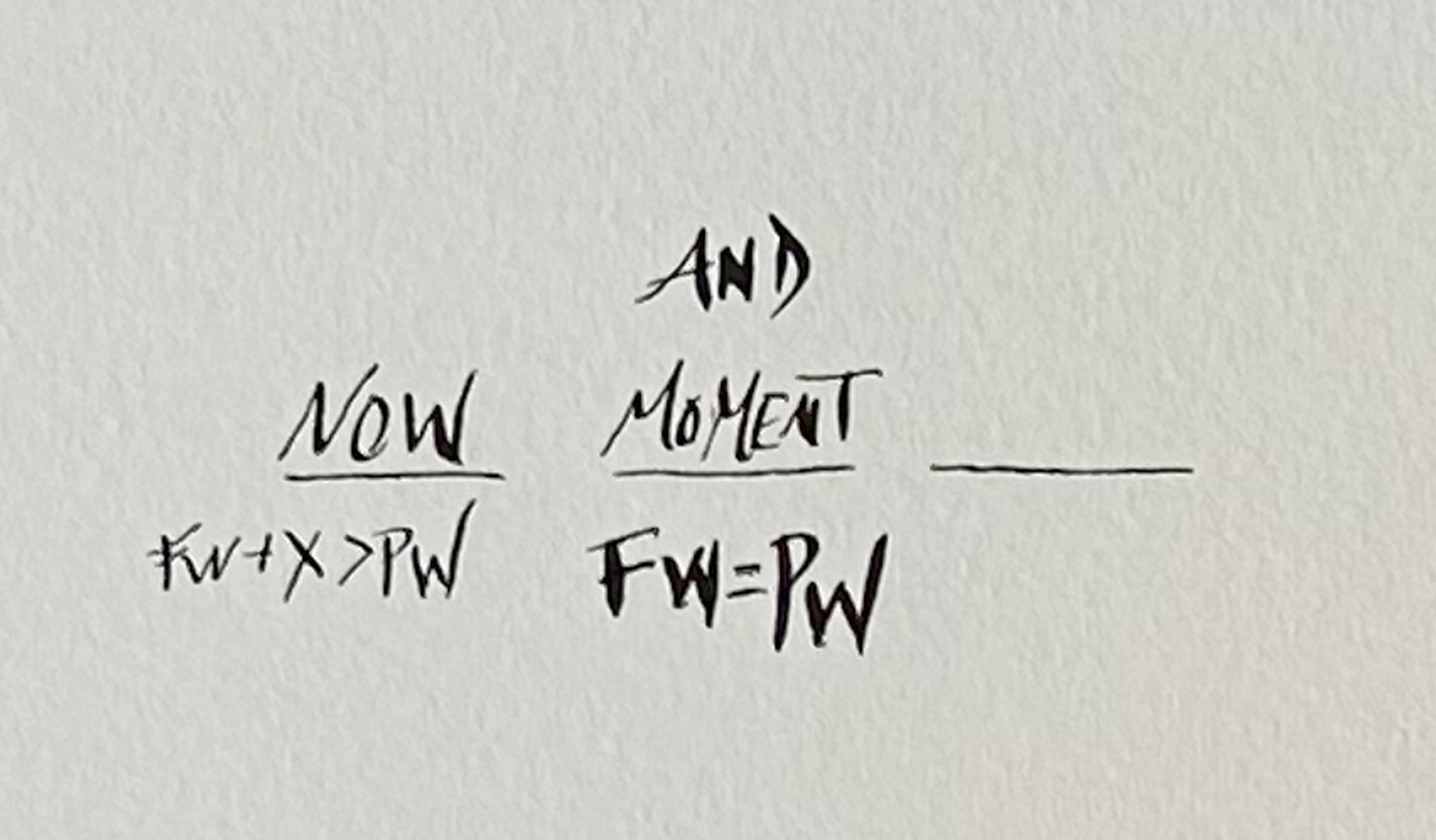

Now, look at this inequality (Future Want is marked as “FW” and Present Want as “PW”):

Before an AND Moment, Future Want is greater than Present Want. It has greater value. When you are not in an AND Moment and just talking about it, Present Want is abstract.16 Before an AND Moment, would you say pancakes and syrup have power over you?

It feels like a silly question because, before an AND Moment, the answer seems obvious. The answer is No. Pancakes and syrup do not have “power” over me. Don’t be silly.

So. Under our “NOW” line, Future Want is the strongest want.

But ... there's more.

It has something called "X" attached to it. You put it there. (Remember that X is something extra you perceive from your choices and actions.) Because you highly value X, you’re always seeking it. Before an AND Moment, you add X where you say it belongs—with Future Want. Before an AND Moment, your goal looks like this:

Future Want always has greater value because you say it does, and it’s easy to say things. Before an AND Moment, your body is not in the presence of Present Want. You only have a faint image of it.17 You can’t see, smell, or touch it, so Present Want isn’t very seductive. You can try to imagine how it feels to want it, but it is a simulated feeling apart from a real-time “readout” from your body.18 In Descartes Error, Antonio Damasio writes:

I believe also that in numerous instances the brain learns to concoct the fainter image of an “emotional” body state, without having to reenact it in the body proper […] There are thus neural devices that help us feel “as if” we were having an emotional state, as if the body were being activated and modified. Such devices permit us to bypass the body and avoid a slow and energy-consuming process.19

The thing is this: because you say X is firmly attached to Future Want, X will find the opportunity to test your resolve. Oh! says X, Future Want has greater value? Let’s put that to the test.

X can make it hard to do things.

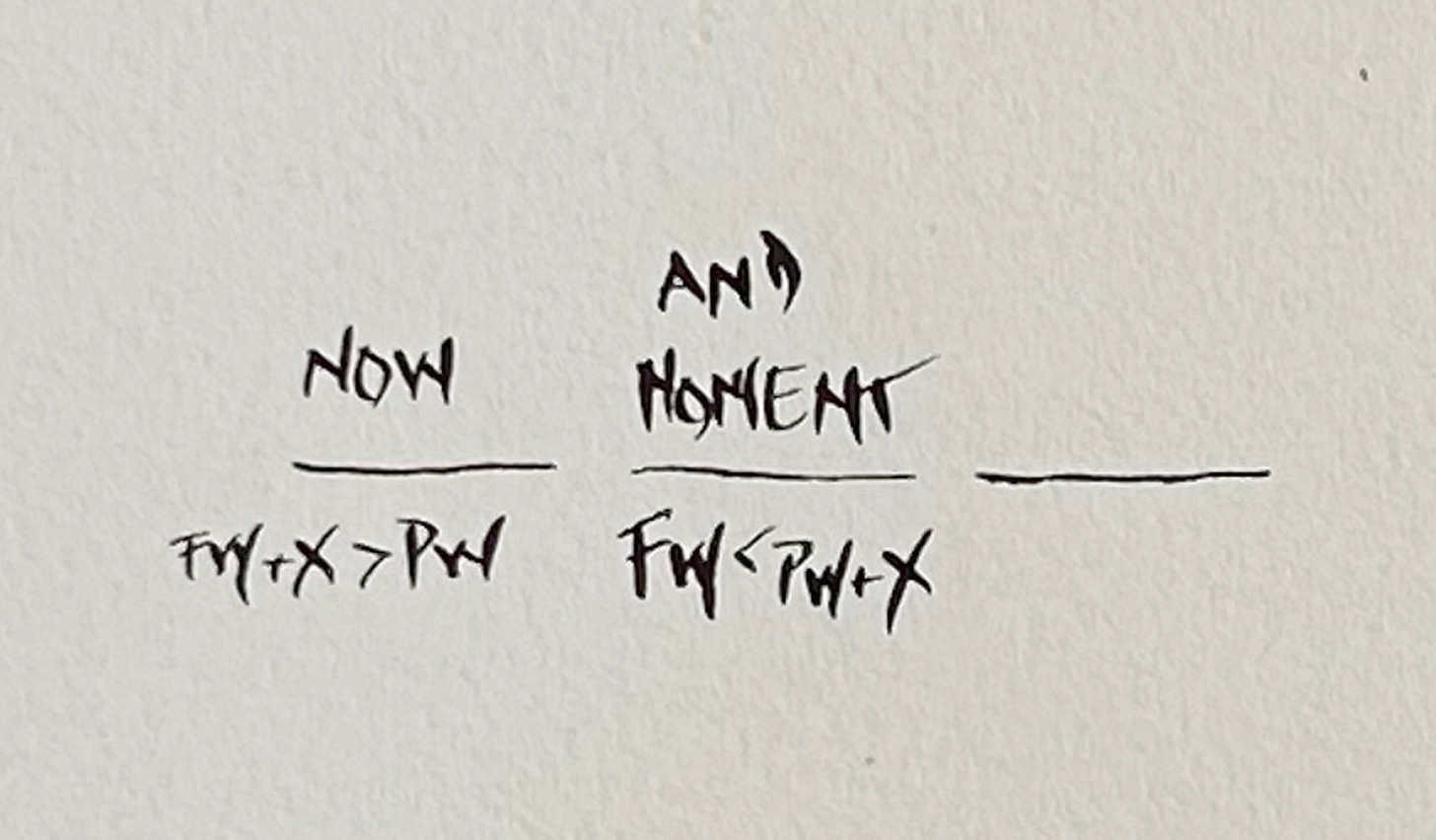

A battle between rivals is hard, yes, and could be represented in a simple way. Instead of Future Want being greater than Present Want (fig 2), they would be equals:

The First Flex. The problem is, once you are in your AND Moment, X will add itself to Present Want, change the quality of Present Want, and make it more attractive and harder to resist. This problem is even more challenging because Future Want requires useful energy, and Present Want gains an advantage when energy stores are low.20

There are two times X flexes itself. The first time is during the AND Moment. X adds to Present Want and—flexes. When X flexes, it becomes very powerful. So, you no longer have just Present Want rivaling Future Want. When X is attached to Present Want, this dynamic is a game changer. It’s such a game-changer that you do something to sabotage Future Want. During an AND Moment, the answer to the “silly” question (would you say pancakes and syrup have power over you?) is yes. Yes, they do. The first flex looks like this:

X keeps your spotlight of attention on Present Want while you mind the body “live” (i.e., in real-time).21 Damasio writes:

Feelings let us mind the body, attentively, as during an emotional state, or faintly, as during a background state. They let us mind the body “live,” when they give us perceptual images of the body […] Feelings offer us a glimpse of what goes on in our flesh, as a momentary image of that flesh is juxtaposed to the images of other objects and situations; in so doing, feelings modify our comprehensive notion of those other objects and situations. By dint of juxtaposition, body images give to other images a quality of goodness or badness, of pleasure or pain.

With Future Want sidelined and in the dark, its image fades from working memory. Future Want is no longer nearly as attractive. It seems like a distant, unachievable future, and the only thing you can see - because of X - is Present Want. You lose sight of your goal.

When your body is in the presence of the real, not simulated, Present Want, you shape, amplify, and sustain the desire for it (body—live!).22 As X increases Present Want, you appraise Present Want as having greater value than Future Want. X calls out to you. X makes promises. During an AND Moment, you choose Present Want when X promises pleasure or relief from discomfort.23

Last night (in our story), you insisted that Future Want will remain your strongest want during breakfast. But in the morning, at the world-famous pancake diner, with the smell of the very best pancakes sweetening the air you breathe, you become less certain of your resolve. When your loved one says to you, the pancakes smell absolutely delicious. Only a fool would pass on them, you say …

Find out—in Part 2.

“Willpower draws on the evaluation of a prospect, and that evaluation may not take place if attention is not properly driven to both the immediate trouble and the future payoff, to both the suffering now and the future gratification, remove the latter and you remove the lift from under your willpower's wings.”

— Antonio Damasio, Descartes’ Error

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. New York, NY: W. W. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt., hereafter cited as HEAM | p 57

rival (n.) | from Latin rivalis […] The sense evolution seems to be based on the competitiveness of neighbors: “one who uses the same stream,” or “one on the opposite side of the stream,” hence in various ways “one who is in pursuit of the same object or resource as another […] It is the hypothetical source of/evidence for its existence is provided by: Sanskrit rinati “causes to flow,” ritih “stream, course;” Latin rivus “stream;” Old Church Slavonic reka “river;” Middle Irish rian “river, way;” Gothic rinnan “run, flow,” | retrieved from https://www.etymonline.com/word/rival

Damasio, A. R. (2010). Self Comes To Mind: Constructing the Conscious Mind. New York, NY: Vintage., hereafter cited as SCTM | p 299, “In the natural course of a day, we inevitably face frustrations, anxieties, and difficulties that throw homeostasis off balance and consequently make us feel unwell, perhaps anguished, discouraged, or sad. […] The state of off-balance homeostasis is neurally represented as an impeded, troubled body landscape.”

Thayer, R. E. (1989). The Biopsychology of Mood and Arousal. New York, NY: Oxford University Press., hereafter cited as BMA | p 8 & 9, “In other words, interpretations of personal problems at any one time appear to be only partially influenced by what is actually happening in the external environment. Also important is how energetic or tired one is at the moment, together with the degree of tension or calmness. While these differences are not large, over time they can be important. This is quite a fundamental idea, particularly in light of the transitory nature of energy feelings. A normal person’s general energy state shifts each day in a predictable cycle that appears to be largely endogenously controlled. Therefore, the same personal problems appear different at ten o’clock in the morning—the high-energy time—than they do at four in the afternoon or eleven at night—the low-energy times. Evidence will be presented in chapter four that these subtle but measurable differences in problem perception are due to an internally shifting biological cycle of energy and the interaction of this cycle with tension.”

Pfaff, D. W. (2006). Brain arousal and information theory: neural and genetic mechanisms. Harvard University Press. | p 15, “Information, by Shannon’s calculation, is maximized in situations of greatest uncertainty. Consider a choice between two events, one of which has the probability of p and the other (1.0-p). If either happens all the time (in this figure, the x axis = 1.0 or = 0), then its informational value is minimized. There are no surprises. On the other hand, If the situation is absolutely unpredictable (p = .5), then information is maximized.”

Hofmann, W., Baumeister, R. F., Förster, G., & Vohs, K. D. (2012). Everyday temptations: an experience sampling study of desire, conflict, and self-control. Journal of personality and social psychology, 102(6), 1318. | “When participants attempted to resist, however, behavior enactment was reduced to 17.4% on average. Hence, self-control reduced the enactment of desire-related behavior from 70% to 17%. […] It is also instructive to examine the strongest desires, defined as those receiving the maximum strength rating of 7 (which was labeled as “irresistible”). When not resisted, these were enacted at a 71% rate. With resistance, enactment dropped to an estimated 26% (Figure 3), indicating that not only did people often resist so-called irresistible desires, but they were surprisingly successful when they did.”

Cyders, M. A., & Smith, G. T. (2007). Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and individual differences, 43(4), 839-850. | “We recently proposed the existence of positive urgency, or the tendency to engage in rash actions when in an unusually positive mood (Cyders et al., in press).” || Um, M., & Cyders, M. A. (2019). Positive emotion-based impulsivity as a transdiagnostic endophenotype (Vol. 197). Oxford University Press. || “research has begun to better appreciate how positive emotions bias decision-making and can lead to many of the same negative outcomes that for years were primarily believed to be connected with negative emotional states.”

HEAM | p 66, “Your brain is always predicting, and its most important mission is predicting your body’s energy needs, so you can stay alive and well.”

BMA | p 77, “However, this research clearly indicates that the seriousness of one’s problems is at least in part an internally determined matter. It appears that in some respects reality changes with circadian arousal rhythms! […] As I have previously discussed, the moods of energy, tiredness, tension, and calmness are excellent indicators of personal resources. Therefore, when a person thinks about a personal problem, he or she also considers present personal resources. This process probably occurs so rapidly that one is scarcely aware of it.”

Solms, M. (2021). The Hidden Spring: A Journey to the Source of Consciousness. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., hereafter cited as HS | p 98, “Freud, you will recall, defined ‘drive’ as ‘a measure of the demand made upon the mind for work in consequence of its connection with the body.’”

HS | p 150, “As I explained before, Freud readily admitted that he was ‘totally unable to form a conception’ of how bodily needs could become a mental energy. He also wrote that this energy was capable of increase, diminution, displacement and discharge, and therefore possessed all the characteristics of a quantity, ‘though we have no means of measuring it’.” || p 152, “You can’t settle for any old body temperature: you must remain within the limited range of 36.5-37.5 °C. If you get much hotter than that, you die; if you get much colder, you die. You cannot allow your core body temperature to equalize with the ambient temperature, as hot water does when you add it to a cold bath. Hot water entering the bath doesn’t remain separate from the cold in a large globule under the tap. But you do – you must, to stay alive – and this requires work. Comatose patients cannot perform such work, and so they die from conditions like hyperthermia; they literally overheat. The same applies to the regulation of blood gases, fluid and energy balance, and many other bodily processes. It even applies to emotional needs, which, as we saw in Chapter 5, are no less ‘biological’ than bodily ones. Remaining within the viable bounds of our emotions also requires us to work: to maintain close proximity with our caregivers, to escape from predators, to get rid of frustrating obstacles and so on. Beyond a certain level of predictability, the work required to do these things is regulated by feelings. The mechanism I have just described is an extended form of homeostasis, and it isn’t complicated.”

Barrett, L. F. (2017, February 17). Extended endnotes for How Emotions are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain by Lisa Feldman Barrett., Unpleasant affect and the body budget, Chapter 4 endnote 39, Some context is: Your affective feelings of pleasure and displeasure, and calmness and agitation, are simple summaries of your budgetary state. Are you flush? Are you overdrawn? Do you need a deposit, and if so, how desperately?” Retrieved from https://how-emotions-are-made.com/notes/Unpleasant_affect_and_the_body_budget | “For some time now, I have been wondering whether unpleasant affect might be the brain’s signal for an unbalanced body budget. For example, unpleasant affect, fatigue, and glucose depletion have similar effects on perception. They lead people to perceive hills as steeper, heights as higher, and distances as longer. The challenge, of course, is trying to figure out what unpleasant affect means (what caused it and what to do about it). Affect, alone, does not provide clear guidelines for action. As discussed throughout the book, this is why it is useful to make meaning from changes in your body budget (and their affective properties) by conceptualizing them as emotions.”

HS | p 155

Ibid., HS | p 98, “Now you see how closely affects are tied to drives; they are their subjective manifestation. Affects are how we become aware of our drives; they tell us how well or how badly things are going in relation to the specific needs they measure.” || Pfaff, D. (2006). Brain Arousal and Information Theory. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press., hereafter cited as BAIT || p 2, “Arousal plays a critical role in the conceptual foundation of ethology. Satisfying the need for an ‘energy source’ for behavior, arousal explains the initiation and persistence of motivated behaviors in a wide variety of species, not just mammals. […] Arousal, fueling drive mechanisms, potentiates behavior, while specific motives and incentives explain why an animal does one thing rather than another.”

Hogan, M. (2021, Jan 23). Alan Watts Quote on The Present and How It’s Not A Result Of The Past. MoveMe Quotes. Retrieved from https://movemequotes.com/sunbeams-15/ | “Everyone automatically assumes that the present is the result of the past. Turn it around, and consider whether the past may not be a result of the present. The past may be streaming back from the now, like the country as seen from an airplane.” — Alan Watts, Sunbeams (Page 14).

Gilbert, D. (2006). Stumbling on Happiness. New York: Vintage. | p 116, “Seeing in time is like seeing in space. But there is one important difference between spatial and temporal horizons. When we perceive a distant buffalo, our brains are aware of the fact that the buffalo looks smooth, vague, and lacking in detail because it is far away, and they do not mistakenly conclude that the buffalo itself is smooth and vague. But when we remember or imagine a temporally distant event, our brains seem to overlook the fact that details vanish with temporal distance, and they conclude instead that the distant events actually are as smooth and vague as we are imagining and remembering them.”

Ibid., p 116, “Just as objects that are near to us in space appear to be more detailed than those that are far away, so do events that are near to us in time. Whereas the near future is finely detailed, the far future is blurry and smooth. For example, when young couples are asked to say what they think of when they envision ‘getting married,’ those couples who are a month away from the event (either because they are getting married a month later or because they got married a month earlier) envision marriage in a family abstract and blurry way, and they offer high-level descriptions such as ‘making a serious commitment’ or ‘making a mistake.’ But couples who are getting married the next day envision marriage’s concrete details, offering descriptions such as ‘having pictures made’ or ‘wearing a special outfit.’”

Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York, NY: Penguin., hereafter cited as DE | p 156, “We conjure up some semblance of a feeling within the brain alone. I doubt, however, that those feelings feel the same as the feelings freshly minted in a real body state.”

Ibid., p 155

BMA | p 77, “Often the problem faced is something that will occur in the future, and the present personal resources may not be the same as will be available later.”

DE | p 159 || HEAM || “You have a built-in ‘spotlight’ of attention that illuminates some things, such as these words, while leaving other things in the dark.” ||| Barrett, L. F. (2020), Extended notes for Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain by Lisa Feldman Barrett., A note for Lesson no. 3, “Little Brains Wire Themselves to Their World.” Context from page 53 is: “Your adult brain can effortlessly focus on one thing and ignore others, similar to a spotlight in the darkness.” Retrieved from https://sevenandahalflessons.com/notes/Spotlight_of_attention ||| “A ‘spotlight’ is a metaphor for how you pay attention to some things but ignore others. Your brain can move your ‘spotlight’ around, so that anything that is illuminated by its beam is processed by the brain, whereas anything in the darkness outside the beam is ignored as unimportant. This model of attention was developed by cognitive psychologist Michael Posner and his colleagues to explain how your brain can shift attention to different objects or in particular regions of space, while not necessarily moving your eyes. You can try this easily by fixating on these words, but shifting your ‘spotlight’ of attention to what is around the words (the objects in your peripheral vision).”

Hofmann, W., Friese, M., Schmeichel, B. J., & Baddeley, A. D. (2011). Working memory and self-regulation. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications, 2, 204-225., hereafter cited as WMSR || p 208, “Once in the focus of executive attention, immediate affective reactions may develop into more full-blown emotions because they are endowed with a richer set of cognitions generated by attribution and appraisal processes (Baumeister, Vohs, DeWall, & Zhang, 2007; Russell, 2003). These accompanying cognitions in working memory may help to shape, sustain, or even amplify the emotional experience at hand (Bradley, Cuthbert, & Lang, 1996).

SCTM | p 53, “In brains capable of representing internal states in the form of maps, and potentially having minds and consciousness, the parameters associated with a homeostatic range correspond, at conscious levels of processing, to the experiences of pain and pleasure. Subsequently, in brains capable of language, those experiences can be assigned specific linguistic labels and called by their names—pleasure, well-being, discomfort, pain. If you turn to a standard dictionary and look up the word value, you will find something like the following: ‘relative worth (monetary, material, or otherwise) merit; importance; medium of exchange; amount of something that can be exchanged for something else; the quality of a thing which renders it desirable or useful; utility; cost; price.’ As you can see, biological value is the root of all those meanings.”

Can’t wait for part two 2️⃣